There’s a certain image most people carry when they think of depression: someone unable to get out of bed, curtains drawn, the world kept firmly at bay. It’s an image reinforced in films, in conversations, in how society has chosen to picture what mental illness looks like. But the reality is far more complicated.

For many, depression doesn’t look like absence. It looks like showing up to work, making plans with friends, and cracking a joke in a meeting. It looks like life is continuing in full view, while an undercurrent of sadness or emptiness runs quietly in the background. This is what’s often described as high-functioning depression, and it’s the kind that hides in plain sight.

Part of the challenge is that the surface tells such a convincing story. Grades get submitted on time, projects are delivered, and birthdays are remembered. From the outside, these markers of stability create the impression of wellness. But what they don’t reveal are the private negotiations it takes to get through the day, the mental bargaining to get out of bed, the exhaustion that sets in long before evening, the quiet sense of disconnection that lingers even in moments that should feel joyful.

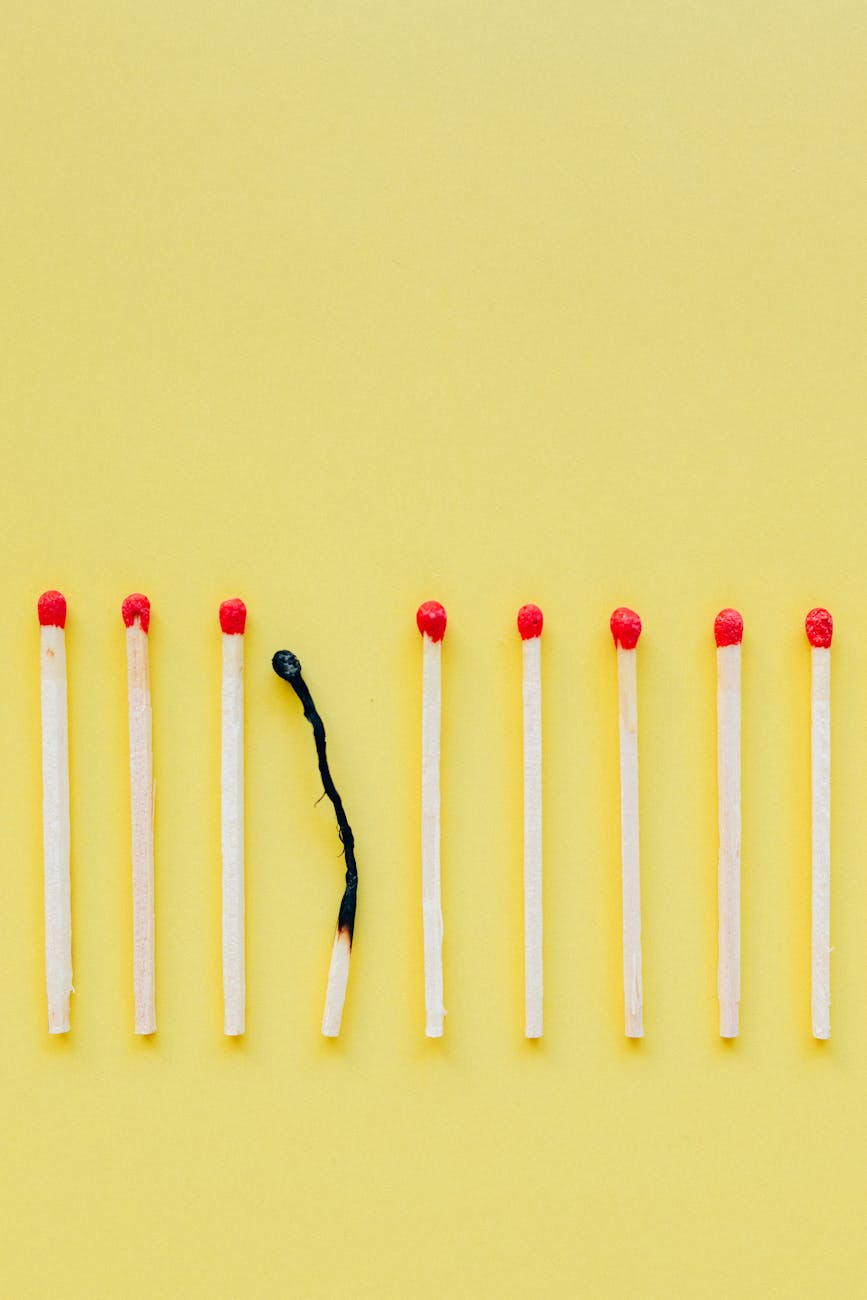

High-functioning depression unsettles the idea that productivity is proof of health. It reminds us that what we see rarely captures the whole picture, and that someone who seems to be managing may still be moving through their days with a weight that isn’t visible to anyone else.

Understanding High-Functioning Depression

The term itself isn’t a formal diagnosis. Clinicians may use different language, such as dysthymia, persistent depressive disorder, or simply depression with milder outward disruption, but “high-functioning depression” has entered the conversation because it captures something many people recognise in themselves or in others.

At its core, it describes a tension: the ability to meet daily responsibilities while privately carrying the weight of depressive symptoms. Someone might attend meetings, care for their family, or maintain social connections, yet feel drained, hopeless, or detached underneath it all. The inner reality doesn’t erase the outer performance, and the outer performance doesn’t lessen the inner reality. Both coexist.

What makes it difficult to identify is that the signs don’t always match cultural expectations. We’re used to noticing depression when it disrupts life in obvious ways, when work stops, relationships collapse, and routines fall apart. However, when the disruption is quieter, when it occurs internally while the external world appears intact, it can easily go unnoticed. Even the person experiencing it may struggle to name it, dismissing their feelings as stress, overwork, or simply “not being good enough.”

This is where high-functioning depression becomes particularly isolating. Without visible markers of distress, support is more difficult to access. Friends may not think to check in. Colleagues may not see any reason for concern. And the individual may continue moving through each day, outwardly composed, inwardly weighed down.

The Everyday Reality

Living with high-functioning depression often means carrying two versions of life at once. There is the outward routine: the alarm that goes off, the commute to work, the conversations with friends. And then there is the quieter version, where each action feels heavier than it should. Getting out of bed is less about feeling ready for the day and more about obligation. Social plans are kept not out of excitement, but because cancelling feels like letting someone down.

This split reality creates a subtle kind of exhaustion. Holding it together in public leaves little energy left for private moments. The smallest tasks, cooking a meal, tidying up, and returning a phone call, can feel disproportionately difficult, even if they’re completed eventually. Over time, the gap between how life looks and how it feels can widen into a sense of disconnection, as if the person is moving through their own story at arm’s length.

Because the struggle is so often hidden, it can also feed into self-doubt. If everything looks fine on the surface, then why does it feel so hard underneath? That question can turn into guilt, a belief that the pain isn’t valid or doesn’t “count” compared to more visible forms of suffering. And so, the cycle continues: functioning outwardly, hurting inwardly, and rarely feeling seen in full.

Why It’s Often Overlooked

Part of what makes high-functioning depression so difficult to recognise is how closely it can resemble “normal life.” When someone continues to meet deadlines, attend gatherings, or keep up appearances, it rarely fits the common picture of what depression is supposed to look like. Instead of being seen as a sign of struggle, the effort it takes to keep going is often mistaken for resilience.

Social expectations add another layer. In many cultures, being busy, productive, and outwardly positive is not just encouraged but celebrated. Admitting to exhaustion, sadness, or disconnection can feel like failing those unspoken rules. As a result, many people learn to mask what they’re going through, sometimes even convincing themselves that their feelings aren’t valid enough to bring into the open.

This invisibility has consequences. Friends and colleagues may overlook the signs, not out of neglect, but because they don’t realise there’s something to look for. Even those experiencing it can hesitate to seek help, worried that their pain doesn’t “count” compared to more visible forms of depression. In this way, the very ability to function becomes part of the trap, making it harder for both the individual and the people around them to acknowledge that something deeper is happening.

How to Support Someone with High-Functioning Depression

One of the challenges with high-functioning depression is that it doesn’t always look like the stereotypes people expect. That’s why support often begins with awareness: remembering that just because someone appears to be doing fine doesn’t mean they aren’t carrying a heavy weight.

Checking In

Checking in is simple, but it matters more than most people realise. A quick message, an invitation for coffee, or even asking “how are you really doing?” can cut through the silence that often surrounds this experience. Sometimes what makes the difference isn’t solving the problem, but reminding someone they don’t have to move through it alone.

Resisting Assumptions

It’s also worth resisting the urge to assume you understand the full story. People with high-functioning depression may mask their struggles well, or they may come across in ways that feel distant or unusual. Instead of rushing to judge, pausing with curiosity and compassion can help open the door to connection.

Sharing Experiences

And if it feels right, sharing parts of your own story can create space for honesty. Vulnerability has a way of softening the walls that depression often builds. Hearing “I’ve been through something like this too” or “I know what it’s like to struggle” can replace isolation with a small, but powerful, sense of belonging.

Encourage Outlets.

When words feel hard to say out loud, having a quiet way to process thoughts can help. Journaling, for example, doesn’t have to be pages of detailed writing; it can be a single line, a note on a phone, or even jotting down one feeling each day. The act itself creates space to reflect, and sometimes, that’s the first step toward clarity.

The Bottom Line

High-functioning depression reminds us that struggle is not always loud. Sometimes it hides in the spaces between achievements, behind polite smiles, or within perfectly ordinary routines. That reality challenges us to widen our understanding of what mental health looks like, not only for others, but also for ourselves.

Maybe the bigger takeaway isn’t just about recognising it in others, but also noticing how often we judge our own worth by how much we can keep going. Functioning doesn’t always mean we’re okay. Sometimes it just means we’ve gotten really good at hiding the struggle.

The challenge, and the opportunity, is to slow down, to check in more gently with the people around us, and to be honest with ourselves when things feel heavier than they look. Because the truth is, you don’t have to fall apart on the outside for what’s happening inside to be real and worth caring about.

Leave a comment